Canadian singer-songwriter Béatrice Martin, who is better known by her stage name Coeur de Pirate, played at Neumos during her North American and European tour. Her debut performance in Seattle was in support of her recently released album, Roses. Montreal-based, she sang most of her songs in French with several in English. Singer-songwriter and actress Sophie Auster opened.

Photos: METZ, Big Ups & Trash Fire @ Neumos

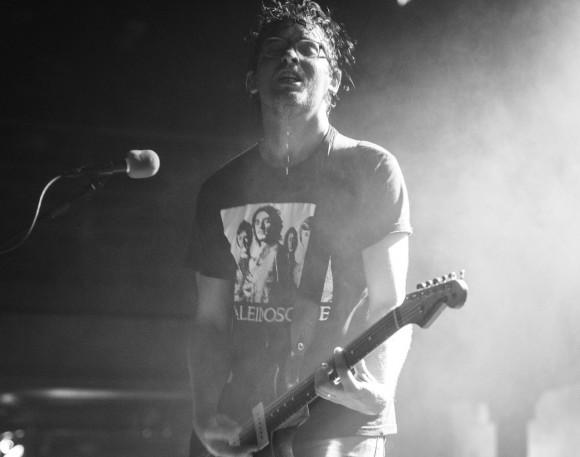

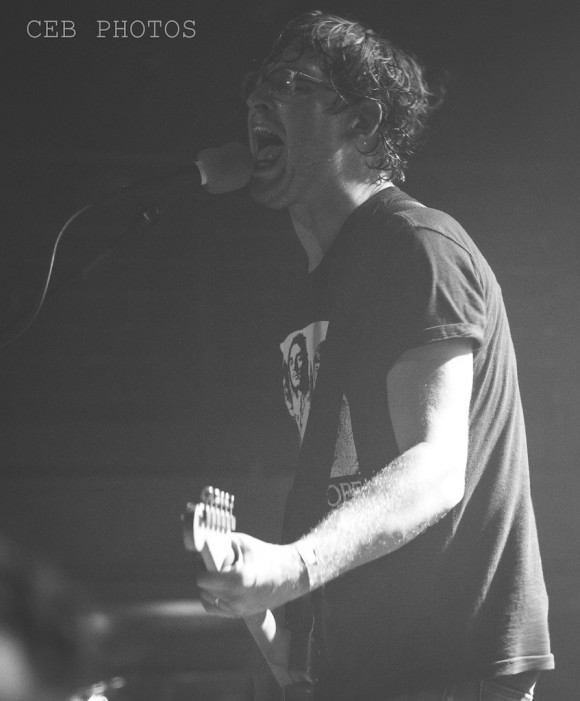

On the summer evening of August 4th, Toronto, Canada’s METZ had the top slot at Neumos. METZ, signed to Sub Pop Records and known for playing exciting punk shows, tour the world beginning on October 16th. Photographers Casey Brevig and Monica Martinez covered the Seattle date, which also had Big Ups and Trash Fire on the bill.

METZ – photo by Monica Martinez

METZ – photos by Monica Martinez

METZ – photos by Monica Martinez

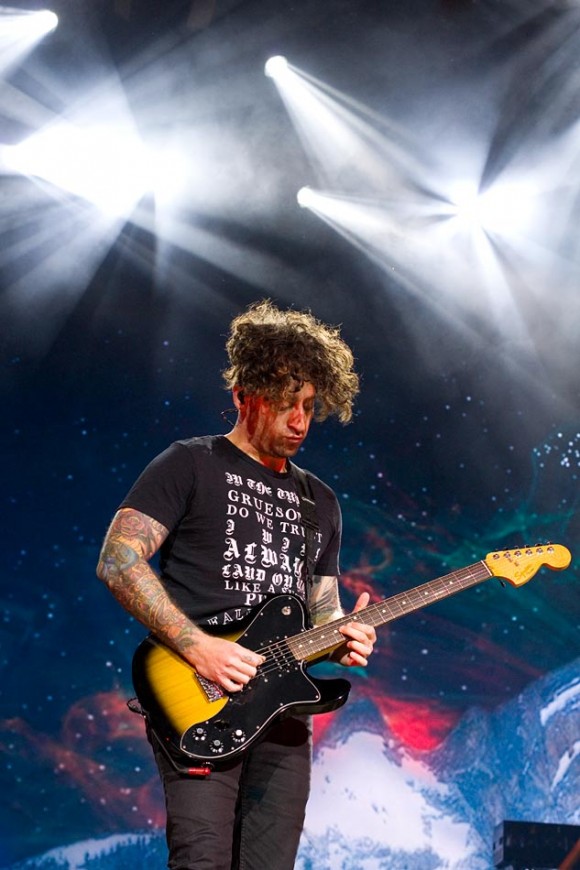

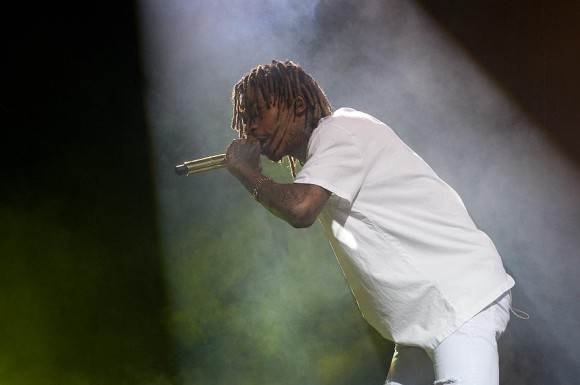

Photos: Fall Out Boy & Wiz Khalifa @ White River Ampitheatre

The co-headlining Fall Out Boy and Wiz Khalifa made an unusual pairing (okay, they’re both from the Midwest), and an appearance at White River Ampitheatre in August. The Boys of Zummer tour took them, literally, all over the United States. Also, Fall Out Boy just announced their line of Halloween shirts. Awesome! And did you know that Wiz Khalifa has his own strain of weed, called Khalifa Kush? What?

All photos by Charitie Myers:

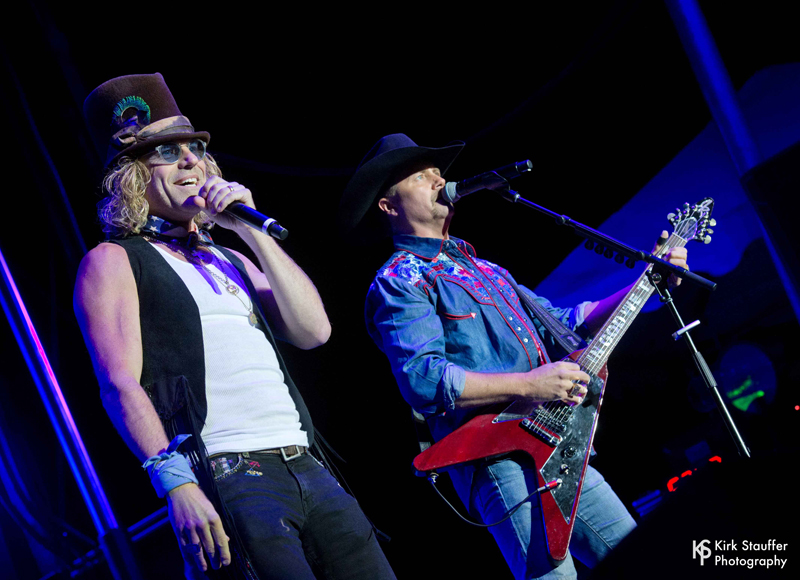

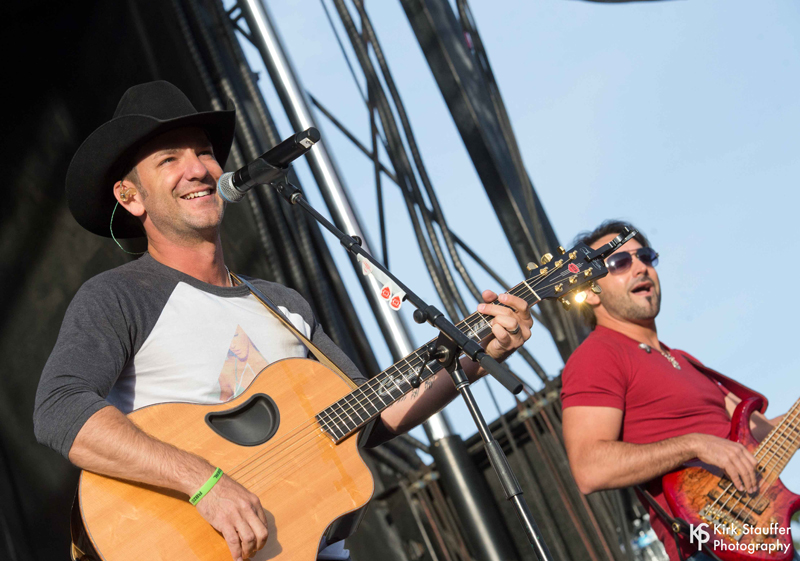

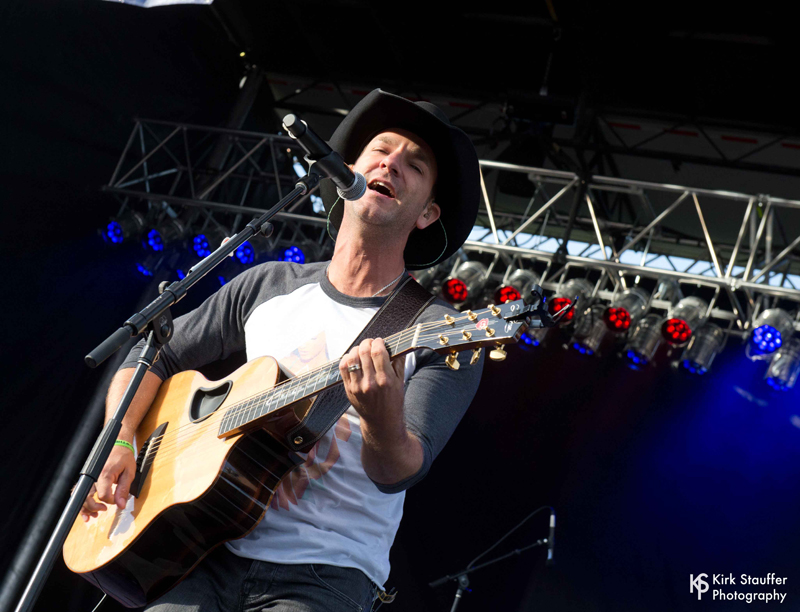

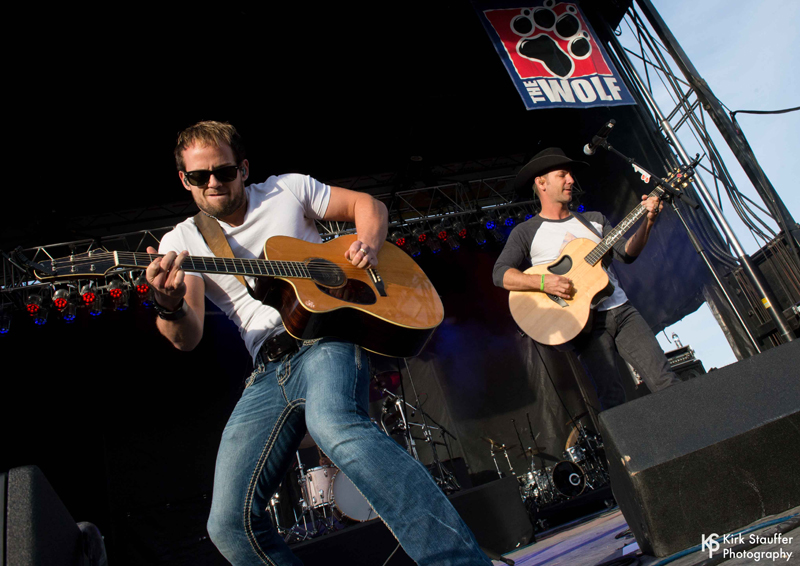

Photos: The Wolf’s Hometown Throwdown

Local country radio station The Wolf (KKWF 100.7) recently held their Hometown Throwdown at Cheney Stadium in Tacoma. The weather was perfect for the all-day outdoor event. The music begin with Mickey Guyton, followed by The Cadillac Three, The Swon Brothers, Craig Campbell, Jana Kramer, and Maddie & Tae. Headliners Big and Rich hit the stage at 9 PM to wrap up the show.

Mickey Guyton – all photos by Kirk Stauffer

Show Preview: Modern Sky Festival @ the Mural Ampitheatre, Sun. 10/11

Modern Sky Festival, a music festival begun in Beijing, China, comes to Seattle this Sunday. Just last year the event came to the States with a production in New York, and now it’s expanding! This year’s lineup, including Gang of Four, Black Lips and Ariel Pink (um, this is definitely intriguing), also brings Chinese bands such as New Pants and Hedgehog into the mix. Plus I see something called Mushroom Bunnies and Friends on the Facebook event page. What’s Mushroom Bunnies and Friends? They sound fun. And I will say this again and again. . . Gang of Four is playing. Gang of Four is playing.

And it’s really cool the festival is using the Mural Ampitheatre, a lovely spot which is way underused.

Lineup! Oh, and be there at noon. This event goes all day:

Gang of Four

Black Lips

Ariel Pink

Mirel Wagner

New Pants

Song Dongye

Hedgehog

Miserable Faith & more