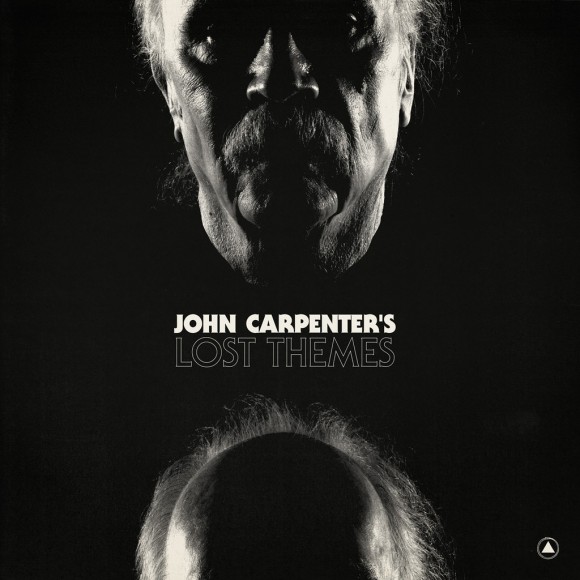

John Carpenter’s Lost Themes

Review by Blake Madden

If you aren’t already a fan of John Carpenter’s films or the themes he’s composed for them, then the introduction of new “lost” ones probably isn’t going to change your mind. In the musical world of 2015 – with every nuance of tone, beat, and style possible – Carpenter’s bombastic arpeggiating synths, hair-metal guitar-tones, and truck-driving anthems of a 1980s future may seem a bit flat – the kind of thing you’d hear playing as a demo for a new synth or version of Pro Tools at Guitar Center.

For the Carpenter completist, however, Lost Themes is a continuation of his singular musical style, one initially forged out of necessity (Carpenter never had money to pay for a professional film score) that eventually became part of the filmmaker’s identity. It’s also a none-too-late realization of his original dream of making music for its own sake, one that has inspired the old dog to some new tricks.

Like his movies, Carpenter’s music is blunt and lean, focused on moving quickly from one backdrop and emotion to the next. Hooks are abundant, ‘nuance’ is for people with bigger budgets. He is the rare artist with perhaps not enough style to match his substance, more than once comparing his own scores to carpeting: “I’m there to support the scene and not get in the way and not annoy you. I put down a nice carpet on your floor so you can walk comfortably and enjoy yourself. That’s my job.”

A lifetime of DIY filmmaking, a forty-year ‘beating’ as Carpenter calls it, will keep you humble and pragmatic. But the beating has taken its toll. Carpenter the filmmaker has slowed to a crawl in the last decade and a half, giving us only 2001’s Ghosts of Mars and 2010’s The Ward, a decline he attributes directly to the exhausting nature of his profession. With his focus removed from films and in a pressure-free environment – working alongside his son Cody and godson Daniel Davies in a basement – Carpenter the musician has re-emerged to record his first ever official album.

Lost Themes (Sacred Bones Records)

Through the opening piano chords and singed guitar lines of album opener “Vortex,” you can almost make out Jack Burton’s Pork Chop Express climbing over another hill on another dark and stormy night, ready to do battle with the forces of darkness. Or Snake Plissken escaping from another maximum-security prison-state (has to be Florida this time). Carpenter isn’t aping his greatest hits so much as leading us to imagine new movies around these themes, movies that, given Carpenter’s advancing age and growing distaste for the process, we’ll likely never see.

While “Vortex” is classic Carpenter, follow-up “Obsidian” immediately gives way to what could be seen as ‘new school’ Carpenter: updated toys, some youthful collaborators who can see a computer screen much better than he can, and plenty of space to work with. Free from the constraints of a film score, Carpenter opens up both his melodic range and arsenal of sounds. Heavy drumming – either recorded live or programmed – abounds on songs like “Obsidian,” “Domain” and “Purgatory.” In place of actors’ dialogue, ghostly synth leads and guitars call and respond back to each other, and multiple synth voices build into multi-layered soundscapes, more overblown than what you might hear in his films.

Each “song” seems to have several movements within it, sometimes only loosely related to each other. We even get rare glimpses of Carpenter in ‘band-riff’ mode, notably on songs like “Domain,” where we’re suddenly transported to the 1983 World Arm Wrestling Championships. It’s simultaneously a bit hokey and a good example of Carpenter’s unpretentious charm: he has forever gotten the most out of tools he’s never quite learned how to use properly.

Which brings us back to the original question of the uninitiated: Can this music (all instrumental) and without a film actually survive and prosper without any other context? Luckily Carpenter has never tried to coax those baloney horn sounds out of his synths, but you would hope that over the years he’d learned to spend a few extra minutes editing his strings, choirs, and leads. It isn’t the case; most still have that stock sound of a not-bad-not-good commercial synth of whatever era he’s in. There aren’t any ‘production’ values or aesthetics to speak of on the album. Even now, and with total freedom, Carpenter is still trying to lay carpet, and still looking over his shoulder while doing so.

Asking or expecting Carpenter to change his spots at this point is moot, and it’s certainly nitpicky for fans already in Carpenter’s pocket. Believe me, I’m one of them. I just wonder if a newer generation will miss out on Carpenter’s idiosyncratic minimalism (they sure love the Drivesoundtrack), his pulsing moodiness, and his melodic twists and turns because they can’t get past that initial ‘band in a box’ sound. Carpenter is too old to care; he’ll never get mistaken for Spielberg or John Williams, so he’ll have to settle for being some weird hybrid of the two, on a shoestring budget till the day he dies. Now he’s indulging a muse he’s kept literally in the background for forty years. I’ll forgive him a bell sound here or there and instead long for all the great non-existent John Carpenter movies these themes could easily belong to.